- Handbook to the Textual Criticism of the New Testament

- Critical History of the Text of the New Testament

- Critical History of the Old Testament

- The Pericope Adulterae, the Gospel of John, and the Literacy of Jesus

- Myths and Mistakes in New Testament Textual Criticism

- The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture

- Literary Forgeries

- The Early Text of the New Testament

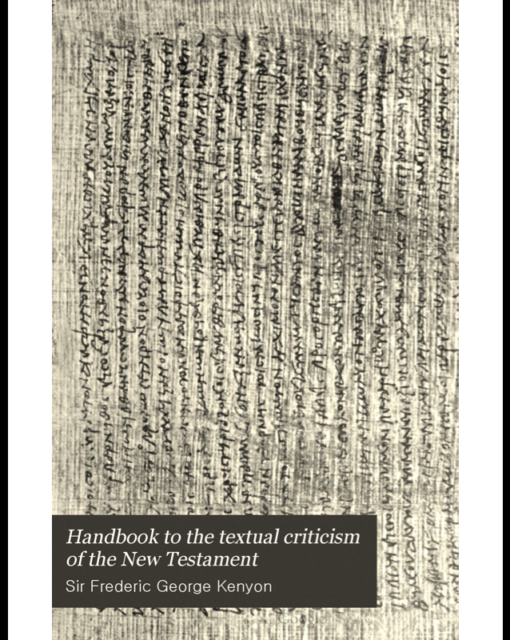

This historic book may have numerous typos and missing text. Purchasers can usually download a free scanned copy of the original book (without typos) from the publisher. Not indexed. Not illustrated. 1901 edition. Excerpt: ... CHAPTER IV THE MINUSCULE MANUSCRIPTS [Authorities: Gregory, opp. ciit.; Scrivener-Miller, op. til.; Westcott and Hort, op. tit.; Nestle, op. tit. ] The uncial period of vellum manuscripts, as will have been seen from the foregoing chapter, extends from the fourth century to the tenth; but for the last two centuries of its course it overlaps with another style of writing, which was destined to supersede it. As the demand for books increased, the uncial method, with its large characters, each separately formed, became too cumbrous. A style of writing was needed which should occupy less space and consume less time in its production.

For everyday purposes such a style had existed as far back as we have any extant remains of Greek writing, and (as we have seen in Chapter II.) it had not infrequently been employed in the transcription of literary works; but it never had become the professional hand of literature, and books intended for sale or for preservation in a library were always written in the regular uncial hand. In the ninth century, however, the demand for a smaller and more manageable literary hand was met by the introduction of a modified form of the running hand of everyday use. The evolution cannot now be traced in all its details, since the extant specimens of non-literary hands (on papyrus) do not come down much later than the seventh century; but in these we can see all the elements of the hand which was taken into literary use in the ninth century, and which is commonly called "minuscule," as opposed to the majuscule (uncial or capital) hands of the earlier period. In the true minuscule hand, not only is the writing considerably smaller than the average uncial, but the forms of the letters are different...